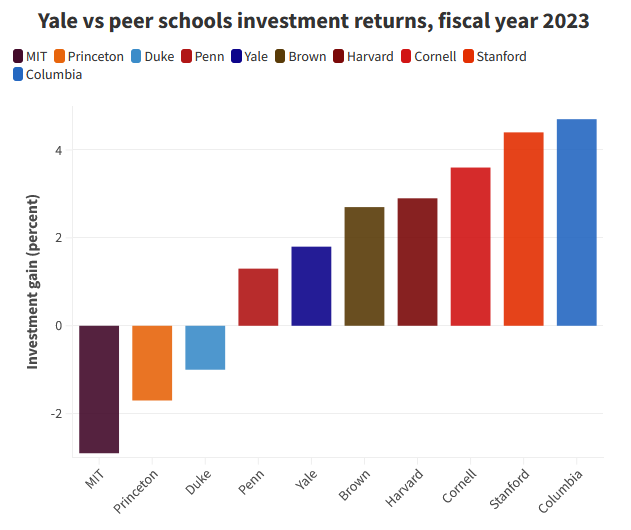

Here’s an update from the Yale Daily News regarding the performance of the Yale endowment relative to the other peer universities. Below is a nice graph of results for the year ending June 30, 2023:

Most people would say these returns sort of stink. The Vanguard Balanced Index Fund (essentially a low cost 60/40 equity/fixed income portfolio) returned over 10% (or 8% more than Yale) over the same time period.

The article even included this great quote:

David Yermack, a professor of finance at New York University’s Stern School of Business, called Yale’s 2023 report “dreadful,” pointing out that from July 2022 to July 2023, stock funds had risen an average of 15.3 percent and bond funds 2.5 percent. If Yale had had a 60-40 mix of stocks and bonds, he argued, “you would have expected something like a 10.2% return.”

“Large institutional investors like Yale should really be passive investors, trying to diversify as much as possible and minimize costs,” he continued in an email to the News. “If Yale had done that last year, its investment returns would have been 8.4% better. Given the starting value of $41.4 billion, that’s about $3.5 billion that’s been lost due to Yale’s overconfidence about being able to identify attractive alternative investments. Even if this strategy has worked for Yale in the past, it gets harder and harder as an investor grows large.”

However, I think the situation is a bit more nuanced than this.

For some background, David Swenson was the previous leader of Yale’s investment team. And he is rightfully credited with revolutionizing the way university endowments are managed. He put in place a framework to invest in alternative assets (private equity, venture capital, hedge funds, etc.), or basically anything that isn’t public equities or bonds.

And Swenson’s investment strategy has worked really well. But why? Well, for a couple of reasons:

#1 – Endowments are REALLY long-term

Yale is over 300 years old. It will likely be around a lot longer than anyone reading this. So the Yale endowment team can afford to invest over a really long time. They can take risks that regular folks cannot. Yale also has a deep bench of wealthy donors who like to give money to the university. Most regular people do not.

#2 – Superior access to the best managers

Question: What’s the difference in skill between the 100 best baseball players in the world and the second 100 best baseball players in the world?

Answer: A LOT.

The top 100 players deliver far more wins for their teams and earn far more money than the second best 100 players.

It turns out that having a “best-of-the-best” skill advantage can translate to huge rewards. And not just in sports.

This also plays out when it comes to active investment managers. The best-of-the-best are worth every penny. The 2nd tier of managers are not nearly so valuable. And the 3rd, 4th, and 5th tier managers are best avoided altogether.

Unfortunately, when it comes to regular people working with the best investment managers in the world, you can generally forget about it. They won’t take your money (or mine)!

Well, who’s money do they take? Yale’s! Yale has long and deep relationships with the best investment managers in the world. Here’s an interesting quote from an article covering Yale’s results from 2021-2022:

Rutgers Business School Professor John Longo gave one possible explanation for Yale’s relative success this year: although Yale and its peer institutions invest heavily in alternative assets, not all alternative assets are equal.

“Yale was the first major endowment to fully embrace alternative investing, so they likely have strong relationships with the preeminent alternative managers, which are often capacity constrained, perhaps providing Yale with a durable, long-term advantage,” Longo wote in an email to the News.

What about last year’s returns?

I’m not too keen to judge Yale’s endowment on the results of one bad year. After all, if you look back over the past 20 years, they have done a great job. And they are in the middle of the pack compared to peer universities.

But I think Professor Yermack is right about one thing… things will continue to be tough for Yale’s endowment because it is so big. At $40+ billion, Yale’s endowment is behind only Harvard’s in size. And as Warren Buffett knows all too well, size can act as an anchor on returns. Here’s what Buffett said a few years ago:

“If I was running $1 million today, or $10 million for that matter, I’d be fully invested. Anyone who says that size does not hurt investment performance is selling. The highest rates of return I’ve ever achieved were in the 1950s. I killed the Dow. You ought to see the numbers. But I was investing peanuts then. It’s a huge structural advantage not to have a lot of money. I think I could make you 50% a year on $1 million. No, I know I could. I guarantee that.”

The reason for this dynamic is simple. Attractive investment opportunities are limited. And a huge pool of capital (like an endowment or Berkshire Hathaway) needs to work very hard to put capital to work in attractive areas. Buffett won’t pick up the phone for any opportunity less than $1 billion and likely neither will the folks at Yale.

Add in the fact that the money managers that invest Yale’s money are also capacity constrained, and it will be tough for Yale to match their historical returns going forward.

Some pension fund managers have even recognized this possibility and switched over to a fully passive investment model, with some pretty great results.

What can we learn

There is no doubt, the everyday investor should not generally try to emulate the Swenson-model of investment management. David Swenson even said this himself. He recommended that most people follow a simple, low-cost, passive investment strategy.

We cannot replicate the Swenson-model because we do not have the same access to world-class money managers, and we do not live forever.

However, we can take consolation in the fact that using evidence based investment practices can make a big difference in our future investment results. We can keep costs low, diversify broadly, take a long-term approach, and stay disciplined. And if we do that, we might even find ourselves doing even better than the Ivy League.