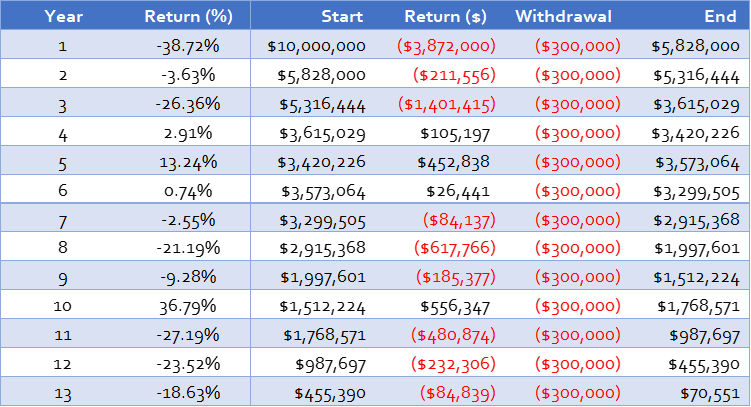

Let’s imagine a fictional couple named Gerald and Ginnie Gerkins. Gerald and Ginnie are 65 years old, retired, and have a $10 million investment portfolio. They like the finer things in life, but nothing too crazy, so they anticipate needing to withdraw only about $300,000 (or 3%) per year from their investments each year. That’s a pretty safe withdrawal rate under most conditions.

However, Gerald enjoys taking risk. He is a former business owner and gains immense satisfaction from growing his net worth. After all, he used this approach for his entire career to accumulate his wealth and it never let him down. As a result, Gerald and Ginnie invest 100% of their portfolio in stocks.

However, luck is not on their side. Coinciding with the start of the Gerkins’ retirement, a perfect storm of high inflation, elevated stock market valuations, and increasing interest rates has induced a slow down in economic activity. The stock market enters a dark period. And so does the Gerkins’ portfolio:

Needless to say, the Gerkins are not happy. Obviously, this is a somewhat sensationalized example, but it’s also well within the realm of possibility. Always remember that unlikely does not mean impossible.

Some readers may point out 1) this series of stock returns is completely unrealistic or 2) the Gerkins likely would’ve reduced their annual portfolio withdrawals much earlier to avoid running out of money. To point #1… this return series actually occurred on the Nikkei 225 from 1990-2002. It’s not hard to imagine a scenario where the S&P 500 endured something similar.

To point #2, I agree that it’s fair to assume that the Gerkins would have made changes earlier, but it’s certainly not a given. For a couple like the Gerkins, taking steps to reduce their standard of living could be a bridge too far. It might mean downsizing their house, losing social connections, and giving up on cherished leisure activities such as travel. As Elon Musk recently said, “…most of the time people don’t change their mind, they just die.” For many, finances are intertwined with reputations, and they aren’t easily severed in times of distress.

Why this matters?

William Bernstein once said, “When you’ve won the game, stop playing.” What he meant by that is you need to take risk to accumulate a nest egg for retirement (play the game), but once you’ve reach your goal (won the game) you should attempt to reduce investment risk as much as possible (stop playing).

In the example above, the Gerkins likely entered retirement with more than enough money to last their entire lives. But instead of pushing back from the table and cashing in their chips, they decided to keep rolling the dice.

Many retirees (including the Gerkins) face asymmetric risk. Let’s imagine that instead of losing all their money in the stock market, the Gerkins doubled their money. Now they have $20 million. Will that improve their life very much? Not likely. Sure, they could spend a bit more, but it’s doubtful that they would be able to make any changes that would cause a significant shift in their well being. However, by losing their initial $10 million nest egg, they are setting themselves up for a much more difficult life.

Suze Orman offers a good example. She has a lot of money, yet she takes a very conservative investment approach involving a lot of boring municipal bonds. She understands that at a certain point in personal finance, playing defense becomes more important than playing offense.

Your stage of life matters

Bernstein also pointed out that your stage of life can make a huge difference in approaching risk:

How risky stocks are to a given investor depends upon which part of the life cycle he or she is in. For a younger investor, stocks aren’t as risky as they seem. For the middle-aged, they’re pretty risky. And for a retired person, they can be nuclear-level toxic.

William Bernstein

Yes, he said nuclear-level toxic! If you are retired and taking on too much equity risk, then it’s possible to blow up your financial situation.

Unlike young people, retirees are no longer working and don’t have a ton of capacity to earn additional money. This economic concept is known as “human capital.” Young people have lots of it in the form of a 30-50 year career. Retirees have very little, often in the form of part-time work. As a result, retirees have a diminished ability to recover from financial setbacks. And that’s why it’s so important to get your financial decisions right in retirement, and get them right on the first try.