I used to be a metals trader for a major bank, so if any interesting stories pop up in that space, I enjoy reading about them. And oh boy, do we have an interesting story for you. Let’s take a look at the nickel market!

For those not aware, nickel is an industrial metal with a variety of practical applications. From stainless steel to batteries, you’ll often find nickel used as an alloy to help protect against corrosion. In fact, Elon Musk, the CEO of Tesla, recently said that sourcing nickel is his ‘biggest concern’ for producing lithium-ion cells for batteries.

Nickel is traded on an under-the-radar exchange called the London Metals Exchange (LME). The LME primarily deals in industrial or base metals and is the main financial market for aluminum, copper, lead, nickel, tin, and zinc. And earlier this month, the LME nickel market blew up.

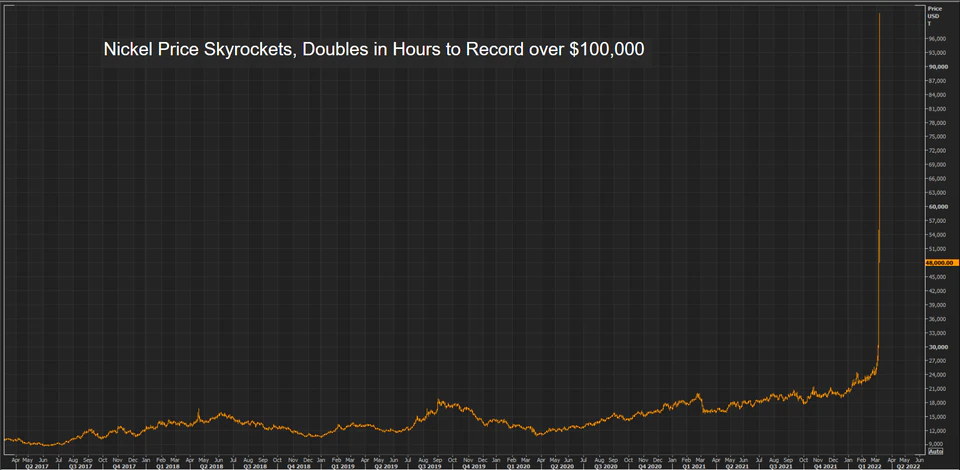

You can read an in-depth walkthrough of what happened here or here. Long story short… on March 8th, the LME was forced to close the nickel market after prices rose above $100,000 per metric ton over the course of 48 hours. For reference, nickel historically trades in a range between $10,000 and $20,000 / MT and usually moves about $400-$500 per day. Here’s a price chart for the past few years:

Ultimately, the LME cancelled all of the nickel trades done during the March 8th trading session. If you bought nickel on March 7th and sold it on March 8th, you were likely sitting on a tidy profit, but not anymore.

What happened?

This is a classic “short squeeze” situation. You may remember this term from the GameStop Incident of Janaury 2021. GameStop’s stock price went from $17.25 to over $500 in the space of a few weeks as retail investors forced some hedge funds out of their large short positions.

The major short seller in this instance is Tsingshan Holding Group, a top producer of nickel and stainless steel in China. Tsingshan is led by Xiang Guangda (nickname = “Big Shot”).1

Guangda actually had a couple good reasons for shorting nickel. First, he leads a firm that produces a lot of nickel, so hedging his financial exposure to the commodity price can help protect his business and reduce the volatility of operating cash flows.

Second, Tsingshan had big plans to ramp up production over the next year, which according to the Econ 101 rules of supply and demand, would put downward pressure on the price of nickel as more product came to market.

The problem was Guangda didn’t account for the fact that there is a big difference between financial and physical commodity markets.

How commodity markets work

Whenever you read about commodity prices in the media, whether it be gold, wheat, oil, or nickel, you are often reading about the “financial” markets. In the case of oil, the two main financial markets are offered by CME Group (WTI) or ICE (Brent). These markets are accessible by pretty much anyone. If you want to speculate on the price of oil, you can get yourself a futures account and start trading.

However, there is also a “physical” side to commodity markets. This side deals with the transport and storage of actual stuff. Physical commodity markets are capital intensive and really only accessible to companies that have infrastructure to handle physical commodity products. For example, you wouldn’t want to take delivery of 1000 barrels of oil unless you had a storage tank, means of transportation, insurance, lots of cash, etc.

The financial and physical markets usually trade in fairly close alignment. However, unlike financial markets, physical commodity markets are constrained by the realities of the natural world. For example, an oil pipeline can only deliver so much oil per day to a given location. So occasionally, the financial markets can become disconnected from the physical market.

And that seems to be the case here. Tsingshan’s large short position was an open secret in the nickel market and the other market players sensed an opportunity. By pushing the price higher, they added stress not only to Tsingshan, but also to Tsingshan’s banking partners. This forced Tsingshan to exit a portion of the short position, which drove the market higher, and continued the cycle.

But as the financial price of nickel went up, it’s likely that the intrinsic value of physical nickel was much lower. There may have been some concern about how the situation in Russia would affect nickel supplies, but overall the physical supply/demand balance did not change very much in 48 hours. And therein we have our disconnect.

The LME can do better

The LME (and the LME’s regulators) deserve a large part of the blame here. Instead of closing the nickel market on March 7th when there were obvious signs of stress, they decided to roll the dice and see what would happen.

Many players are justifiably upset. By cancelling the trades on March 8th, the LME in effect sided with Tsingshan and its creditors. Picking sides is verboten when you run a market system. Fairness is foundational. If market participants can’t be assured that the market is fair, why would they participate?

Cliff Asness, the founder of AQR, has led the charge in excoriating the LME over this. His view is if the market was open on the 8th, the trades should be honored, full stop. And I agree with him. It’s not the LME’s job to pick winners and losers, but rather to implement a set of rules that everyone can agree on and then let market forces handle the rest. Here’s an interesting quote:

One of our key responsibilities is to serve the physical traders. If we allowed the trades to stand, we would have to say that the price of nickel is $80,000-$90,000 and that would not seem rational to the physical market. And we could have placed significant stress on a number of our core members.

Matt Chamberlain (CEO of LME)

You’ll notice that Chamberlain references the disconnect between the financial and physical markets and he shares my belief that physical markets won’t support $100,000 / MT price level. However, that’s funny because what was obvious on March 8th, was also obvious on March 7th. Yet the LME didn’t intervene and cancel trades from March 7th or even shut down the market. This leads me to believe that the market disconnect argument is really a red herring.

The last sentence of the quote identifies the primary concern of the LME. By not cancelling the trades, some core members of the LME would likely become insolvent. And that could lead to the LME’s failure. So in this case, LME management seems to have chosen survival over fairness?

What’s next?

Unfortunately, the LME has a track record of running into major issues. They had a tin crisis back in the 1980’s, the Sumitomo copper incident in the 1990’s, and they have struggled with issues around aluminum financing deals distorting the physical supply/demand balance for about the past 10 years.

We’ll have to see how the nickel market behaves going forward. The LME introduced price limits for the first time in its 145 year history. Nickel can now only trade up or down 5% from the previous closing price (the other metals have a wider range). The LME reopened the nickel market again on Wednesday March 16th, and prices promptly went limit down. The LME also experienced some electronic glitches and had to cancel a few more trades.

Whatever happens next, there is an opportunity for another exchange company to make a move. CME Group already has a well regarded copper market, so it’s logical that they might explore adding contracts for the other industrial metals2. In that case the LME could be in for a rough future. You can’t expect to anger a large portion of your customer base and have bright prospects for success.

1I find it hilarious that a guy nicknamed Big Shot is at the center of this, it’s just too perfect!

2CMEGroup already has an aluminum futures contract, but it’s not widely used.