Here’s an interesting situation to consider when maximizing retirement savings options:

Taylor has maxed out her 401(k) contributions for the year. She doesn’t have a lot of extra cash on hand, but does have a taxable brokerage account with $50,000 of Apple stock in it. Unfortunately (from a tax standpoint), Taylor’s Apple stock has appreciated quite a bit and the cost basis in her brokerage account is only $10,000. So should Taylor sell some of the Apple stock to fund a Roth IRA contribution?

Some people might say, “no way!” However, let’s dig a little deeper.

If we assume that Taylor is in the 15% capital gains bracket and pays Virginia state taxes (5.75%), then she’ll need to sell about $7,794 to fund a $6,500 Roth IRA contribution and pay $1,294 of marginal taxes due on the associated realized capital gains.1

Now let’s compare what happens going forward if we assume a 10 year time horizon and a 6% return (broken out into 4.5% from price appreciation and 1.5% from dividends).

The future value of the Roth IRA = 6500 x (1+0.06)^10 = $11,641.

The future value of the portion of the taxable account that matches the Roth IRA = 7794 x (1+(0.015 – 0.015 x 0.2075) + 0.045)^10 = 7794 x (1.0569)^10 = $13,553. Remember that dividends received in a taxable account are taxable in the year received. In this example, the “tax drag” causes the after-tax return in the taxable account to drop from 6% to 5.69%.

Now we also need to account for embedded capital gains taxes on the taxable account piece. The original cost basis was 7794/50000 x 10000 = 1559. If the taxable account were sold at the end of the 10th year, the taxable gain would be 13553 – 1559 = 11994. And the tax due on that amount would be 11994 x 0.2075 = $2,489.

After paying the tax bill, the future value of the taxable account would be 13553 – 2489 = $11,064. This is $576 less than the Roth IRA account. In this case, selling the Apple stock – even though it is highly appreciated – to fund the Roth IRA would yield a better result.

What about a step-up in basis?

In the previous example, I ignored any potential for a step-up in cost basis on the taxable account. Obviously, if Taylor expects her heirs to received a step-up in basis, the results will shift in favor of holding her Apple stock. The amount of the shift is the $2,489 of terminal capital gains taxes we calculated earlier. Instead of coming in $576 behind the Roth IRA, the taxable account will come out $1,912 ahead.

Another way to think about it… if Taylor expects a greater than 23% (or 576/2489) chance of dying at the end of 10 years, then it might make sense to hold onto her Apple stock. We could even go a step further and use actuarial tables to calculate a probability of Taylor dying at the end of 10 years and then compare, but I’m not going to go into that here.

What about different appreciation rates?

In the previous example, the stock position was highly appreciated. Stock positions with less growth will favor selling now to fund the Roth IRA.

What if Taylor’s Apple stock has only appreciated 10%? In that case, she would need to sell $6,625 to fund her $6,500 Roth IRA contribution and pay $125 for the associated marginal taxes.

Assuming the same time horizon and return metrics from before, the future values look like this:

- Roth IRA = 6500 (1.06^10) = 11641 (same as before)

- Taxable account (with step-up) = 6625 (1.0569^10) = 11521

- Taxable account (no step-up) = 11521 – 1141 = 10380

In this case, the Roth IRA outperforms the taxable account even with the step-up in basis. At a 6% return, Taylor would need to live about 6.5 years to justify funding the Roth IRA contribution.

What else?

The portion of future returns that come from dividends can also effect our decision. A lower dividend yield relative to total return will favor holding the appreciated taxable position. The reason for this goes back to the “tax drag” mentioned earlier. If there is no return from dividends, there is no “tax drag.” A common example of this is Berkshire Hathaway. If you own Berkshire stock and expect to hold it until your death, it’s almost exactly the same as holding it a Roth IRA from a tax standpoint. In that case, you would not want to sell it to fund the Roth IRA.

Time also gets a say. Longer time horizons will favor funding the Roth IRA, but only if you don’t plan on a step-up. If you don’t think you’ll be forced to sell the position and can thus plan on a step-up in 20+ years, then a longer time horizon will favor holding the appreciated position.

A final factor to consider is the type of appreciated position and what you’ll replace it with. For Taylor, we assumed she owned an individual stock (Apple). The future return/risk profile of an individual stock will almost certainly look a lot different than a highly-diversified index fund. If you own a large amount of an individual stock (say from an old employer), then it might make sense to sell some in favor of investing in an index fund inside a Roth IRA, which would help reduce portfolio concentration.

What about Roth Conversions?

We can also carry this analysis over to Roth conversions. One choice investors need to make when doing a Roth conversion is to pay the tax on the conversion directly from the pre-tax IRA/401(k) or from a separate taxable account. As a general rule, paying the taxes from a separate taxable account is best. But what if you need to sell an appreciated stock position to do so?

Let’s say Taylor wants to convert $100,000 from her IRA to her Roth IRA. Again, she has little free cash, but has her $50k of Apple stock!

The tax bill on the conversion would be about $100,000 x (0.22 + 0.0575) = $27,750. We can simply look at this like a large Roth contribution. Taylor would need to sell $33,273 of Apple stock to fund the tax bill on the conversion as well as $5,523 of associated capital gains.

The future values look like this:

- Roth IRA = 27750 x (1.06^10) = $49,696

- Taxable account = 33273 x (1.0569^10) = $57,861 (with step-up)

- Taxable account = 57861 – 10625 = $47,236 (no step-up)

Just as we discovered with the Roth IRA contributions, the decision to fund Roth conversion taxes using an appreciated stock position will hinge on a these key variables (in order of importance):

- The likelihood of a future step-up in basis (lower favors funding Roth)

- The initial appreciation rate (lower favors funding Roth)

- Future dividend yield (higher favors funding Roth)

- Time horizon (it depends on the step-up)

- The nature of appreciated position (it’s complicated)

What about an HSA?

If you have a health savings account (HSA), then the analysis shifts a little further. Unlike Roth IRAs, HSA contributions are tax deductible at ordinary income rates. Let’s assume that Taylor is in the 22% federal bracket for ordinary income and Taylor can make a $3,875 HSA contribution. Everything else is the same as the original example.

The future value of the HSA = 3875 x (1.06^10) = $6,940.

To fund the HSA, Taylor needs to sell $4,646 of Apple stock and owes $771 of taxes. However, by making an HSA contribution, Taylor will save 3875 x (22% + 5.75%) = $1,075 of taxes in the current year. If Taylor chooses to forgo funding her HSA, then in effect she will only have 4646-1075 = 3571 of remaining capital2 to invest in her taxable account.

And the future value of the taxable account looks like:

- 3571 x (1.0569^10) = 6210 (with step-up)

- 6210 – 1096 = 5114 (no step-up)

Even with a 400% appreciation rate (which is fairly high for most people), an HSA will outperform, regardless of the step-up. And if you play around with the inputs, it becomes clear that it’s almost always a good idea to sell an appreciated stock position in favor of funding an HSA if you don’t have any other sources of cash. The value of the HSA’s upfront tax deduction should be hard for anyone to turn down. A Roth IRA can make sense in some cases (e.g. low appreciation rate, low chance of future step-up), but an HSA will almost always make sense.3

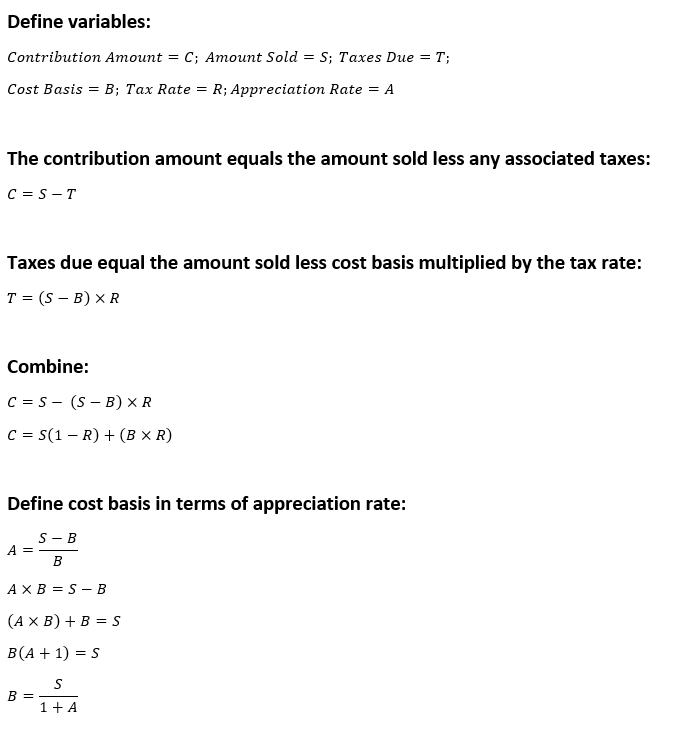

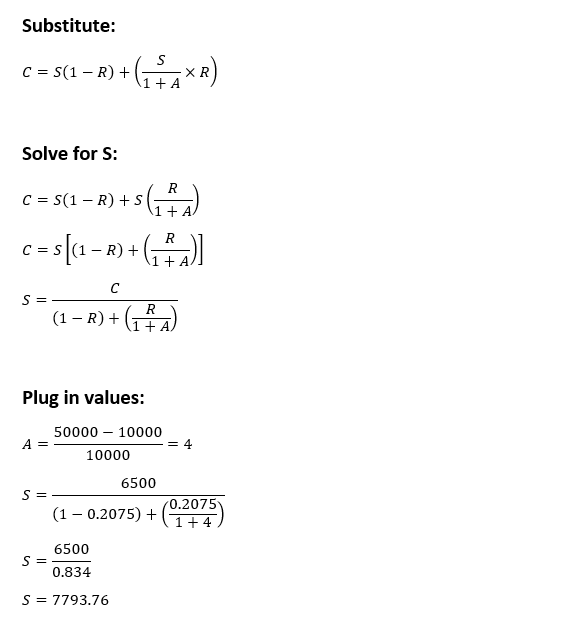

1 Algebra can help us calculate the amount needed to sell. For those readers who enjoy math, I’ve included a quick walk-through below.

2 I ignored the tax effect of having to sell in order to meet the higher ordinary income tax bill. This would have only a modest effect.

3 I’m assuming readers already have an HSA. Deciding whether or not to use an HSA-based health plan to begin with involves an entirely different analysis.